Bussey Bridge Train Disaster

Bussey Bridge

March 14, 1887 dawned gray and cold in Dedham, Massachusetts. It was a snappy Monday morning with the temperature at about 34 degrees. Shortly after 6:00 a.m., Boston & Providence Railroad engineer Walter White and his fireman Alfred Billings steamed their engine, the D.B. Torrey, the short distance from the Dedham engine house to the impressive stone edifice that was the Dedham depot of the Providence Railroad.

Engineer White, a 31-year veteran on the Dedham to Boston run, cautiously backed into the train of nine open-platform, red-varnished coaches that made up the 7:00 A.m. train to Boston. The yardman dropped the pin into the coupling and White and the Torrey were tied to the head end. This was the only day in the week when he would trail nine cars, for on Mondays the passenger load required one extra car.

The run was familiar to White. He’d covered the same route for three decades, and today, as usual, he would follow the 6:10 to Boston. His passengers would be businessmen, workingmen, and store girls - about 100 by the time they left Roslindale, the community halfway between Dedham and Boston’s Park Square Depot.

The D.B. Torrey was a trim little 440 American Type locomotive, the mainstay of American railroads of the 1880’s. She was built by the Rhode Island Locomotive Works in 1880 and weighed 35½ tons. She had just been fitted with a new stack, slightly smaller than her original, and this caused her to steam with a little more difficulty than usual. But this was the only thing out of the ordinary that morning, and it meant simply that Billings would labor more with the coal scoop and White wouldn’t have the power normally available.

Promptly at 7:00 a.m., the train of partially-filled wooden coaches chugged out of Dedham Square over the bridge across High Street and into the outskirts of town. It steamed through snow-covered meadows and crossed the iron bridge spanning Mother Brook. Billings watched the boiler pressure gauge needle dance between 90 and 105 pounds, down a bit from the normal pressure that powered the Torrey.

Back in the coaches, Conductor Myron Tilden and his assistants William Alden and Webster Drake busied themselves taking tickets, while brakeman John Tripp, Winfield Smith, and Elisha Annis remained alert for the engine whistle that would send them to the end platforms to wind the brakewheels. Their effort, added to the air brake on the Torrey, would be more than sufficient to stop the train under normal circumstances. The day of the automatic air brake was just dawning, and while mainline trains were equipped with such systems, branch trains had yet to be modernized.

At each of the closely spaced stations - Spring Street, West Roxbury, Highland, and Central - the train picked up more of its human cargo. Five stops after leaving Dedham the train stood in Roslindale station. By then, nearly 200 passengers occupied the eight coaches and one combination baggage and smoking car coupled to the end of the train.

White’s watch showed him seven minutes late. The timetable called for a 15 minute run from Dedham to Forest Hills, about a mile and a half from Roslindale. The extra car, the cool morning which made wheel bearings stiff, and the poor steaming of the Torrey had combined to lose time from White’s schedule. Regardless, he was better than halfway into Boston on a routine Monday morning in March.

Slowly, White notched the Torrey’s throttle out. The engine barked through a shallow earth cut just east of the station and began the slight downgrade toward Forest Hills. Out of the cut and onto a high embankment the train rattled above the frozen ice and snow covered meadows below.

About a quarter mile ahead, the single-track Dedham Branch crossed South Street on a spindly iron truss bridge known as the Bussey Bridge. It took its name from the old Bussey family farm that later was to become a part of the would-famous Arnold Arboretum. In earlier days, as a wooden bridge, it was sheathed in tin to prevent it from catching fire. The iron structure, which replaced it, was still known as the Tin Bridge.

The Bussey Bridge, toward which 200 souls in nine fragile coaches were heading, was by any standards, a peculiar structure. It crossed the street at an incredibly oblique angle, its spindly iron trusswork bridging a gap of some 120 feet between high granite abutments. So sharp was the angle of the span that the floor beam which ran from the center of the truss on one side rested on the end of the truss which supported the other side of the bridge. Its design was such that certain structural members carried a disproportionate share of the load of every locomotive and car passing over the structure. And this was a violation of the laws of physics and mechanics that would not be tolerated forever.

That March morning, Engineer White approached the old Tin Bridge at a cautious speed. It was a habit, arising from restrictions placed on the bridge prior to its rebuilding in 1876.

There was no indication whatever of any danger as the D. B. Torrey and her nine red coaches rolled toward the bridge. To the engine crew the bridge appeared as solid and safe as ever. White could see meadows stretching away on either side of the embankment, their pale, frozen grass surface punctuated occasionally by stands of bare maples and elms.

The familiar rumble White had heard as his engines crossed innumerable bridges during his career filled his ears as he passed over Bussey Bridge that morning. As the Torrey reached the Boston end of the span, however, White felt a sudden jarring of the engine’s front end, and as the drivers reached the far abutment there was a strong shock unlike anything he had ever felt passing over the bridge.

Immediately he looked back and saw the first car off the track, careening drunkenly behind him. His blood ran cold as he watched the second, third, and fourth cars dancing insanely, trailed by an ugly cloud of smoke and dust where five more cars loaded with passengers should be crossing the bridge,

Instinctively he knew that his train, save the first three or four cars, had gone through the bridge. In the seconds it took for the awesome spectacle to unfold, White’s hands pulled the reversing lever - the fastest way to bring the Torrey to a halt. By now the force of the writhing cars and their human cargo had snapped the coupling at the tender and the Torrey was free.

As the engine came to a halt, White’s reflexes told him there was nothing he and his fireman could do. He knew there was a Dedham-bound train with Engineer Tim Prince in the cab waiting for him at Forest Hills. It was loaded with laborers headed for Dedham to work on a bridge project. He knew too, that these husky workers might well mean the difference between life and death to those trapped in the coaches which lay in a heap beneath where the Bussey Bridge once stood.

Before the engine stopped, White threw the reversing lever ahead, yanked the throttle out, and the Torrey lunged forward again. White grabbed the whistle cord, and the polished brass steam whistle atop the Torrey’s dome screamed in anguish as she roared toward Forest Hills.

Woodcutters in the woods beside the tracks and residents along the line were stopped by the piercing wails of the whistle. They watched as the Torrey raced down the track, her engineer and fireman frantically waving and pointing back in the direction she had come from. That some kind of calamity had occurred was obvious.

In what seemed like seconds, the Torrey was at Forest Hills. White and Billings yelled to station agent William Worley that a train had gone through the bridge and to send Jim Prince’s three-car train with its laborers to the scene.

Immediately Prince had his engine barking at full throttle up the branch toward the ill-fated commuter train. White leaped from his cab and ran into the small frame depot where he ordered Worley to telephone for doctors and ambulances.

Five minutes later he was again aboard the Torrey, headed back to the scene to give what help he could to the dead and injured.

What met them when they returned was a ghastly panorama. Three cars teetered on the frozen roadbed, their wheels torn from beneath them, underbodies and platforms smashed to kindling. Behind the third car the roof of the fourth lay on roadbed, torn from the rest of the car body, which was some 50 feet below. The fifth through the ninth cars were either at the bottom of the embankment or in the chasm where the bridge had stood.

The rear car, which had been the smoker, was smashed, turned upside down. The next car was thrown on its side and stove in; the next car dropped square on its wheels and stood upright. The succeeding two cars were telescoped and lapped onto each other and a part of the sixth car was wedged between the telescope and the embankment. All the cars were smashed and broken, twisted and entwined with the iron beams and girders of the bridge. Broken rails, twisted and jagged bars of iron, and splintered wood combined with badly mangled dead and injured in a scene of horror.

Within minutes, spurred on by White’s alarm, help was arriving from everywhere. Residents and shopkeepers, workers and doctors from Roslindale arrived in time to extinguish one small fire and help in removing the injured. Hundreds worked feverishly to remove the wounded. A special train carrying doctors, hastily assembled by railroad officials from the professional buildings around Park Square Depot in Boston, arrived to render medical aid.

When all the passengers had been removed the dead and near-dead numbered 23. Most of the dead had been killed instantly. Some of the injured survived a few hours, one several days. Over 100 were injured, more than half of them seriously.

What caused this terrible disaster? The Boston Globe that evening speculated that a weakened span failed under the weight of the train.

The Massachusetts Board of Railroad Commissioners convened the day after the wreck and sat until April 4, gathering facts upon which to determine the cause. What it heard from survivors, railroad officials, the builder of the Bussey Bridge, and outside engineering experts was a story of an incredible collection of circumstances culminating in the tragic collapse.

The primary cause was determined to be a pair of iron hangers which formed an integral part of the supporting network of iron rods making up one of the two trusses upon which the rails rested. Improperly designed and manufactured, they weakened gradually with the passage of time and failed catastrophically that morning. The weight of the Torrey snapped the hangers, and the bridge immediately began to disintegrate as the train crossed the span.

The parade of witnesses described how the Boston & Providence in 1876 entered into a contract with one Edward Hewins, representing the Metropolitan Bridge Company, to rebuild the bridge. Testimony further revealed that he alone was the Metropolitan Bridge Company. When pressed on this point by the commissioners, Hewins testified it had been his intention to organize a bridge company at the time but never got around to doing it. The two trusses which made up the ill-fated bridge were actually fabricated by two separate iron works. The Commissioners found that the railroad had never investigated the Metropolitan Bridge Company and that no one involved in making the contract really knew enough about iron bridge building to pass intelligently on the structure’s design and specifications. In fact, it was generally admitted during the hearings that the company didn’t even employ an expert to review the design of the bridge once it had been built.

One railroad employee who had inspected the bridge regularly was a machinist who was not trained to look at key structural parts for signs of failure.

Six years earlier the Commission had recommended a series of structural tests for the bridge, which were never conducted. Crossties were spaced too far apart for safety. The bridge was not equipped with guardrails to catch the wheels of a derailed train and guide them safely across. And, tragically, the Westinghouse automatic air brake was not in operation on the train even though it was becoming more common on the nation’s railroads. Had it been in use, it might have prevented the fatal plunge of coaches into the chasm following the separation of the train from the engine.

Fire, the real horror of most train wrecks of the era, didn’t occur because the B & P followed a policy of bolting its coal-burning, car-heating stoves to the floor and bolting the doors shut, thereby, eliminating the possibility of hot coals igniting the wooden wreckage.

The wreck was a calamity for the Boston & Providence, which for almost twenty years previously had not had a train accident resulting in injury or loss of life to a passenger.

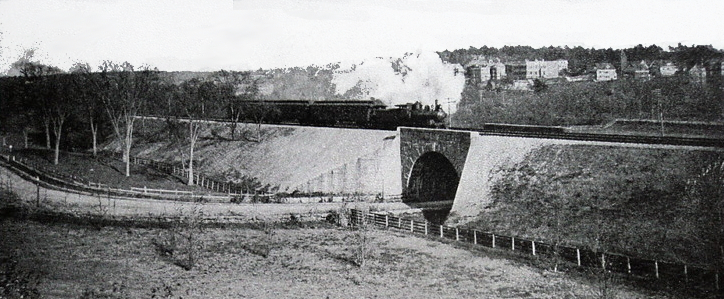

Today the Boston & Providence is long gone, along with its Dedham Branch to West Roxbury. Where once stood the Dedham depot, a municipal parking lot serves Dedham shoppers. Trains still cross South Street in Roslindale on the Penn Central’s Needham Branch. But the Bussey Bridge they use is a solid, substantial granite arch, which has safely carried passenger and freight trains since before the turn of the century. It stands as a stone monument to the hapless passengers on the 7:00 A.M. train and the quick-thinking engineer whose fast action that Monday morning in March saved so many lives.

Written by Edward J. Sweeney. Originally published in Yankee Magazine, March 1975.